The New York Times

By ALAN FEUER

Published: October 16, 2001

There were 1,500 pigeons packed into traveling crates, and the Knights of Columbus taproom smelled like a barn. It was race night and the birdmen talked to one another about storm fronts and prevailing winds. They talked to their birds.

They synchronized their race clocks and tagged their pigeons with numbered rubber bands. They drifted toward the bar to make their boasts and lay their bets. Someone bragged about his slate-roofed coop -- a recent import from Belgium. Behind their beer cups, the other birdmen frowned with lust.

At midnight, the crates were stacked in a trailer and the birds were hauled 400 miles from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, to Cadiz, Ohio. The race would start in the morning when the pigeons were freed at 8 a.m. Flying at 55 miles per hour, with a tailwind and a bit of luck, it would take them about seven hours to return.

For a pigeon racer, there is no greater joy than watching the heavens suddenly offer up a homer returning to its loft. This is a pleasure unknowable to the ordinary man. ''If I wasn't flying pigeons, I'd be dead,'' said Frank Viola, 82. ''My birds are my life.''

There are perhaps a few hundred pigeon racers in New York City, and earlier this month nearly all of them entered the Frank Viola Invitational at the Knights of Columbus lodge in southern Brooklyn. Breeders from around the country -- Oklahoma, Florida, Texas, Hawaii -- enter their birds in the race. It is considered the Kentucky Derby of the pigeon racing set.

In the 1950's, it was hard to walk down a street in Bensonhurst or Coney Island without a flock of pigeons twinkling in the sky like a handful of falling dimes. The last 50 years, however, have been tough on the pigeon game. Teams have disbanded; new racers are hard to find.

The sport, racers say, has gotten too expensive. They spend as much as $10,000 a year on entry fees, E. coli medication, handmade coops and specially blended feeds. That's not to mention computerized clocks, veterinary visits and travel to training grounds.

''If you've got birds on Staten Island and you're training in Jersey, you're talking about $15 a day just in tolls,'' said Joe Green, a computer technician who entered several birds in the Viola race. ''It's $500 in medication a year. Another $300 for the clock. Forget about it. These things are like racehorses. They're the thoroughbreds of the sky.''

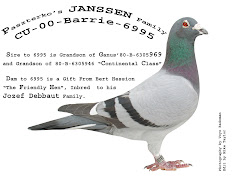

A pigeon race is more complicated than any horse race. The course is invisible and the racers never see their birds in flight. The pigeons are trucked from a central spot to a ''liberation point'' typically 400 to 500 miles away. The birds are freed as a flock and head for home. The racers await them at their coops.

When a pigeon lands, the racer plucks the rubber band from its foot, and the band goes into a plastic capsule, the capsule into a metal clock. The clocks automatically assign a time to every capsule ''banged'' inside them by the turn of a handle. The birds fly different distances from the liberation point to their coops in the city. The winner is the pigeon with the best air speed in yards per minute.

Pigeon racing originated in Europe and has been traced back as far as the Roman Empire. The sport flourished in the 19th century in Belgium and Holland, and took root in the United States as soldiers returned from World War II.

The birds are born pathfinders and can make their way home from 700 miles away. ''They have iron deposits in their brains that act something like a gyroscope,'' said Dr. Catherine Toft, a professor of ecology at the University of California at Davis. ''Geese use the stars to navigate, but pigeons basically have tiny compasses in their brains.''

The men who race them can spend an entire evening discussing the merits of Antibac and Pigeonguard vitamins or whether the Staf Van Reet breed of birds truly is the greatest sprinting strain. They say things like, ''Yul Brenner was a pigeon man'' or ''That bird of yours pretty much walked home, didn't he?'' When their pigeons are flying, they pass up weddings and funerals. They pass up quiet nights at home with their women and wait in their coops, staring at the sky.

Frank Viola is a birdman's birdman. He has paintings of his favorite champions hanging on his walls. Mr. Viola has been known to study a pigeon's eye with a jeweler's loupe and pronounce him a winner. He can pick his own birds from a flock of 20 as they pass above at 30 yards.

He has a racing team of 100 birds in his coop in Coney Island, and this year entered 70 in the invitational he has organized for the last 10 years. On Oct. 7, when his birds were freed, he set up shop in his cluttered apartment. He watched the Weather Channel, taking updates from callers stationed along the course.

''Waiting for the birds'' is a full-fledged social gathering. Mr. Viola has a glassed-in observation booth outside his coop. The booth, about the size of a bus stop, is outfitted with folding chairs, a space heater, a desk, a clock, a phone.

He started his vigil at 3 p.m. on race day as thrilled as a 6-year-old on Christmas Eve. Pete Viola, his nephew, sat beside him, glancing at the clock. Their friend Butch D'Amato paced outside the booth, his eyes glued to the sky.

They waited. The skies were clear. A jet headed toward J.F.K. Then a smudge banked above them. It could be . . . yes, it was -- a bird. Mr. D'Amato tensed then slackened. ''Ah, it's just a street rat,'' he said of the common city pigeon.

When recalcitrant racing pigeons arrive, racers send up birds called chicos to cajole them toward the coop. The chicos are like avian chase planes; they lead stray pigeons to the loft. Mr. D'Amato had a cage of chicos at his feet. He plucked one out and held it like a football, ready to toss it into work.

He didn't need it. As he stroked the chico, a pigeon appeared. It came from nowhere and landed on the roof. It bobbed its head and waited. It sat there just a foot above the coop.

''That's my bird!'' Mr. Viola shouted. ''He came right down like a bullet! Come on, boy! Come on! Go on! Go on! Get in the coop!''

Mr. Viola nodded at his pigeon. Mr. D'Amato sprinkled birdseed on the coop. The pigeon watched the men with its vacant pigeon stare. Pete Viola was on the telephone: ''Uncle's got a bird!''

Frank Viola said, ''Oh, my heart is beating, Butchie!''

Mr. D'Amato clucked and cooed: ''My heart is beating, too!''

When the pigeon finally came down, Mr. D'Amato snapped the band off its foot and stuck it in a capsule. Then he banged the capsule in the clock. He came out smiling, pumping his arm. Like a touchdown scored in the final quarter.

The official race time: 38 seconds after 3:11 p.m.

Pete Viola hit the phones. Staten Island, no birds. The Bronx, no birds. Queens, Long Island, other Brooklyn coops, no birds. Frank Viola had the winner -- the first time he'd won his own race. He jumped to feet and hollered. ''Hoo, hoo! Hoo, hoo!''

From inside his observation booth, he sounded like his birds.

Photos: Frank Viola, the birdman's birdman, in his coop in Brooklyn. His bird won the Frank Viola Invitational for the first time.; Racers calibrated their computerized clocks, above, before each race. More than 1,000 birds, packed into traveling crates before being taken to Ohio, were signed in for the Kentucky Derby of pigeon racing. (Photographs by Aaron Lee Fineman for The New York Times)(pg. D1); A handler tagged a racing pigeon in preparation for the Frank Viola Invitational. In the race, the birds flew from Ohio to New York. (Aaron Lee Fineman for The New York Times)(pg. D7)

Read more ...