The New York Times

By DEVIN SMITH

Published: October 26, 2003

SHIRLEY— LESS than 70 miles from New York City, where pigeons are widely regarded as feathered rats, fanciers gather to haggle over the price of thoroughbred racing pigeons.

Every week, on Wednesday nights and Sunday afternoons, as many as 60 people crowd into the back room of the Pigeon Store at 60 Northern Boulevard in Shirley to discuss breeds, eat doughnuts and occasionally buy a bird.

''Pigeons are a big deal around here,'' said Joan Schroeder, who works at the store and breeds her own birds. ''I nearly couldn't squeeze into the auction room last week there were so many people.'' Auctions are also held at the Pigeon Store's second location, in Lindenhurst.

On Long Island, an estimated 2,500 pigeon owners breed, fly and race more than 300 types of birds. The Nassau-Suffolk Pigeon Fanciers Club, which has about 100 members, holds three shows and a swap event each year at the Holtsville Ecology Center. Its biggest event, to be held on Nov. 15. this year, showcases about 2,000 birds, none of which would be found on a city street corner.

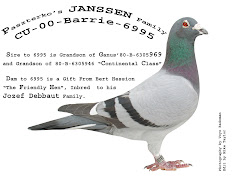

''The general public will always assume the pigeons we breed are the same as the ones they see in the park,'' said Deone Roberts, the spokeswoman for the American Racing Pigeon Union in Oklahoma City, a national organization that promotes pigeon racing. ''But that's like comparing a thoroughbred to a plow horse, or a champion show dog to a street mutt.''

There are some 1,000 pigeon clubs in the United States with membership ranging into the tens of thousands, the racing union estimates. Although no organization keeps track of the exact number of clubs, fanciers with decades of experience estimated that there are 12 to 15 on Long Island alone. Some towns on the Island require licenses for pigeon lofts, but fanciers said that that stipulation was honored mostly in the breach.

As with horses, the variety of pigeon breeds seems endless, but at the Pigeon Store's auctions, homing pigeons -- birds capable of returning to their home lofts from after journeys of thousands of miles -- constitute the largest number of sales.

Then there are the tipplers, or birds that can stay aloft for more than 15 hours; fancy birds, the result of crossing different breeds to create rare and elegant strains; and rollers, or pigeons that tumble as if shot in midair, only to spring back to life and surge skyward.

At a recent auction, iridescent green and gray homing pigeons fluttered nervously in their cages. As big-band music filtered through overhead speakers, a handful of men, mostly elderly and white, appraised the birds, preparing to stock up for the fall racing season, which runs from Labor Day to early November. Some unsentimental fanciers even buy large homing squabs for the dinner table.

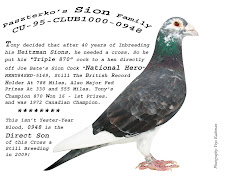

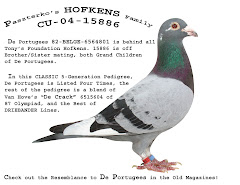

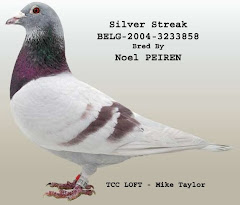

The average price for a racing pigeon is about $5, but the cost of a bird with a champion lineage can rise into the hundreds, if not thousands.

On the day before a race, which may range from 100 to 800 miles, fanciers gather at their local club with the birds they plan to register. They load the birds onto the club's trailer for the trip to the race's starting point, called the liberation site. For Long Island fanciers, the sites are usually somewhere in Pennsylvania, Ohio or New Jersey, depending on the race mileage.

At dawn the next morning, club representatives release the birds and watch as they wing their way eastward. The bird that flies at the fastest average speed, measured in yards per minute using Global Positioning data, from the liberation site back to its home loft, is the winner. Most of the birds fly at speeds of 35 to 60 miles per hour, depending on the wind direction and velocity.

''Racing pigeons are little athletes,'' said Ms. Roberts, the racing union spokeswoman. ''They're racehorses with wings.''

Some fanciers have equipped their lofts with high-tech clocks and electronic landing pads that read transmitters on their birds' leg bands and automatically clock them in. The owners then take a printout of the times to the club sponsoring the race.

Tradition-bound fanciers do all this by hand. They wait for their birds with string paddles, or poling sticks, which resemble lacrosse sticks and are used to capture the birds when they arrive. The owners remove the leg bands and put them in capsules, which are placed in the slot of a time-stamp clock. When the fancier turns a crank, a capsule is stamped with the arrival time. Capsules are held in the clock's innards until the clock is opened at race headquarters.

But sometimes the birds don't come back at all. Predators, power lines, storms and strong winds all take their toll. ''You hate to lose them, but you can't beat nature,'' said Val Matteucci of Hicksville, a fancier for 40 years and the secretary-treasurer of the International Federation of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers, organized in 1881. ''If they stop in a tree or hit a wire and fall to the ground, they can become prey very easily.''

Humans have used homing pigeons for more than 5,000 years to send messages over great distances. The United States Army used tens of thousands of birds in both World Wars and in the Korean War when radio silence was necessary or when communications had been disabled. Now pigeons are used by the military as a double-check on chemical-weapons sensors, much as canaries were once used by miners.

Scientists still don't know how homing pigeons find their way, but they believe that the birds pick up cues from the position of the sun and from geomagnetic fields.

In Europe, pigeon races often carry six-figure cash prizes, and each year, the Million Dollar Pigeon Race is held in South Africa. In the United States most fanciers compete only for diplomas and trophies, although the Snowbird Classic, which is sponsored by the Fernando Valley Club of Sun Valley, Calif., is expected to offer $100,000 in prize money for the first 10 finishers. The race will next be run on Nov. 20, 2004.

Gary, a fancier from Mastic Beach who insisted that his last name not be printed because he did not have a license for his 350-bird loft, said that feeding pigeons has some fringe benefits.

''Their droppings are the best fertilizer,'' he said. ''You scrape it up and throw it in the garden. In a few days, it pushes up tomatoes like forget about it.''

Photos: John Leone, far left, checks in for an East Meadow Pigeon Club race. There are an estimated 2,500 pigeon fanciers and 12 to 15 clubs on the Island.; For the East Meadow club's 300-mile race last month, pigeons were transported in crates to the starting point in Somerset, Pa. (Photographs by Phil Marino for The New York Times)

Read more ...