The New York Times

By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr.

Published: August 20, 2001

Correction Appended

BEERSEL, Belgium, Aug. 18— The boys down at the Beersel pigeon-racing club were not happy Thursday evening when Eric Limbourg strolled in -- late, as usual.

It wasn't just the clothes, though he did stand out. The club, the back of a bar at an RV campground, makes most dog tracks look like Ascot on Derby Day, and a T-shirt over a beer belly passes for evening dress. Mr. Limbourg wore an orange polka-dot shirt, a blown-dry coif and a gold chain.

Rather, it was the pile of pigeon panniers he was packing, and the wad of cash.

Mr. Limbourg entered 25 flying nags in Saturday's 250-mile race from Vierzon, France, and bet 25,000 Belgian francs -- about $600 -- on them.

Afterward, he dismissed it as ''just a training race'' to keep his yearlings in shape. He's bet as much as $5,000 on one race, he said, and has won up to $16,000.

But since the night's typical pigeon owner -- mostly retirees and blue-collar workers -- had laid down between $15 and $115 on his or her stable, Mr. Limbourg's entry skewed the pool.

So did the intimidation factor.

''Now none of us have a chance,'' grumbled one member at the registration table. ''He's the champion.''

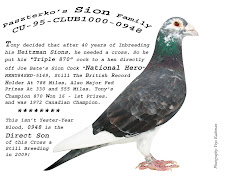

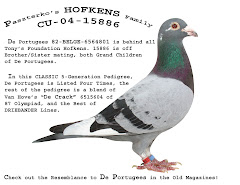

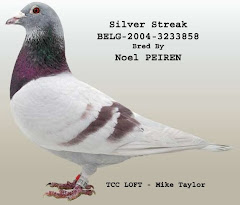

Indeed he is. Belgium's 60,000 breeders in a population of 10 million make it the Kentucky bluegrass country of pigeon racing, and Mr. Limbourg, 43, is the big Colonel Sanders of squab-on-the-wing. Known as Wonderboy since he began winning trophies in 1977, he says his best birds sell to Taiwanese and Japanese buyers for up to $90,000. Others say he's being modest for tax reasons; top birds fetch double that.

In the suspicious world of pigeon fanciers, when a man is that kind of kingpin, one word comes to mind: dope.

''Who knows?'' said Philippe Matton, the bar owner who has run the Beersel club most of his life, shrugging. ''Maybe he's got something they can't find yet.''

Mr. Limbourg vociferously denies it. He wins consistently, he said, because he has good blood lines and training techniques, and he cleans his coops himself. He spends eight hours a day on his 350 birds, keeping his bank job to forestall the tax man from treating them as more than an amusing hobby. He divulged one secret: he keeps his newborns in the dark for four months (simulating winter stimulates feathers).

It's such calculations that set Roger Arnhem, secretary general of the Royal Belgian Society for Bird Protection, against the sport.

''Sport?'' he said dismissively. ''The bird is the athlete. The breeders are not all bad men -- but they're interested in money. There's no love for the animal.''

Pigeons were used as newsboys by the ancient caliphs and pharaohs. The names of some gallant World War I messengers are still recorded in histories of Belgium, above whose fields they soared -- or fell to the other side's shotguns.

But in top-level racing, money corrupts such purity of heart. There are so many ways to cheat that the Olympics and Tour de France look clean by comparison.

It's the rare weightlifter, for example, who quaffs cortisone against late-season moulting. It's the rare gymnastics coach who tries to pocket his tiny protégé and substitute a lookalike. And a bike racer who scammed in a few miles by car at night would probably be noticed.

The sport has remarkably rigid rules and arcane gear -- all aimed to keep owners honest.

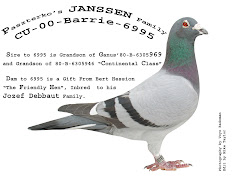

There is, for example, a special machine just for slipping on numbered rubber leg bands. The sealed clocks each owner takes home -- into which his birds' leg bands must be inserted as soon as they arrive -- are set to a radio signal beamed from Frankfurt.

For a Saturday race, the birds must be turned in at local clubs in midweek.

That allows transport time, but also renders stimulants useless. When their panniers -- the baskets they travel in -- burst open, some contenders have been found drumsticks-up from caffeine overdoses.

After banding, they go into special baskets, which go on special trucks, which go on special trains. Owners are kept away. Race officials on the trains may secretly re-band the birds or write code words under their feathers. A contestant calling in a winner may be told: ''Lift his left wing and read me what you find there.''

The coop of a consistent winner like Mr. Limbourg will be visited by veterinarians who will corner some of his champions, do whatever it takes to get them to turn over feces samples, seal the evidence in a sterile container and speed it to a lab.

A confirmed positive means a three-year suspension. (For the owner. The athlete may fare worse -- see below.)

Mr. Limbourg said his coop has been ''controlled'' 10 times. He failed once, six years ago, but beat the rap in court, arguing that a jealous rival could have slipped a mickey into the basket watering troughs at the club. He suspects eyedrops with banned anti-inflammatories.

Though amiable, he is a wary man. ''It's possible,'' he admitted Thursday night, that he had deliberately waited until the last minute to register.

''He's smart,'' said Mr. Matton, 70, the bar-owner/president, who was racing only two pigeons that night. ''He knows other people will leave if they see him.''

And Mr. Limbourg, despite brooding stares from the bar's other benches, didn't leave for two hours, until only Mr. Matton was left, waiting for the truck.

''Keeping an eye on his birds,'' Mr. Matton said, pulling down his own eye for emphasis. ''He's nervous, that one.''

By 1 p.m. on Saturday, race day, Mr. Limbourg, back home in Brussegem, north of Brussels, was showing all the sideline cool of Bobby Knight.

He paced the balcony of his coop, which is two stories tall and as long as a nine-car garage. A rival 15 miles to the south had called at 12:59 to brag that his first bird had landed. But the winner is the one showing the highest average speed, so Mr. Limbourg could still take the prize.

Hunching his shoulders, grimacing and clenching his fists, he scanned the sky as if he was expecting incoming mortar rounds, not birds.

Visiting pals, also top breeders, who had arrived in a Jaguar and a BMW, waited well back on the lawn for fear of spooking arrivals.

When one appeared overhead, Mr. Limbourg clucked ''Come, come, come, come, come!'' into the heavens and rattled a food pan. The first bird alighted casually at the coop at 1:16. Mr. Limbourg stalked it in stiffly, averting his eyes and keeping his arms out to prevent second thoughts about freedom.

Moments later, he shouted out the leg number to an uncle booking them in.

(Later, he would grumble that better clubs use microchips that would save him 20 seconds.)

Back on the balcony, he switched to swearing when a bird decided the roof was close enough to consider home. He threw other birds out to encourage it to quit dawdling, and swore louder as it hopped around, mulling it.

After half an hour, with 20 birds in, he calmed down. Calling other rivals, he estimated that he had taken second place and that his first 15 birds might each win something from the betting pool.

As for the missing five? Well, that can be a sad story.

Mr. Limbourg said his would just show up later. But Mr. Arnhem, of the bird protection society, said his workers are often called to pick up exhausted racers that drop into fields and gardens.

When they trace the owners through the leg bands, ''we get the same answer every time,'' Mr. Arnhem said. ''They say, 'It lost, it's no good, we don't need it. You can just do this . . .' '' (he twists his fists saying ''krrriiik'' -- the unmistakable sound of bird-neck-wringing) ''and make a soup, with petits pois.''

Photos: Eric Limbourg, a champion pigeon breeder and racer, holds one of his birds at his coop in Brussegem, Belgium. Pigeons burst from baskets on a truck near the French border during a race on Saturday morning. (Karim Ben Khelifa for The New York Times) Map of Belgium highlighting Beersel: The pigeon-racing club in Beersel, Belgium, is in a campground bar.

Read more ...