The New York Times

By RANDY KENNEDY

Published: March 5, 2002

In the annals of strange subway stories -- some pure urban legend, some alarmingly real -- there has always been a menagerie of animals.

Stories of alligators roaming the tunnels, of pet snakes loose on trains, of rats tough enough to survive the third rail. There have been eyewitness accounts of live chickens, on their way from poultry market to soup pot, escaping from sacks and running amok through the cars. Recently, someone posted a story on the Internet about a man in the subway walking a dog that was being ridden by a cat, the dog and cat dressed in matching Uncle Sam hats. (The story was accompanied by a photograph to prove that it was not made up by Dr. Seuss.)

But one subway animal story has been so persistent and widespread that it simply cried out to be investigated: the case of the train-riding pigeons of Far Rockaway.

A little more than a year ago, a motorman and a conductor on the A line, which terminates at the Far Rockaway station, swore to this reporter that it was true. They said it was common knowledge among longtime riders and those who worked on the line. Pigeons, they said, would board the trains at the outdoor terminal and step off casually at the next station down the line, Beach 25th Street, as if they were heading south but were too lazy, or too fat, to fly.

The inquiry began the other afternoon, when the question was put to a car cleaning supervisor at the terminal. He appeared suspiciously nervous about the subject. ''Oh, no,'' he said. ''Our trains have no pigeons.''

But Andrew Rizzo, 44, a cleaner sweeping in a nearby train, looked around and smiled as if he were finally going to get to reveal his secret.

The birds ride the trains all the time, he explained, motivated not by sloth but by simple hunger and ignorance: when the trains lay over at the terminal to be cleaned, for about 20 minutes, pigeons amble through the doors, looking for forgotten crumbs. But being pigeons, they do not listen for the announcement that the train is leaving, and the doors close on them. They ride generally for one stop, exiting as soon as the doors open again.

''If you don't know what's going on,'' said Mr. Rizzo, pushing his glasses up on his nose, ''you'd think they knew what they were doing. It's a little freaky.''

Mr. Rizzo has a soft spot in his heart for pigeons, who helped him make a living in Central Park in the late 1980's when he was less gainfully employed. He would wear straps with tiny cups of birdfeed on his arms and head and would soon be covered with pigeons, Hitchcock-style. He would put out a donation box, and pull in $200 a weekend. ''I still feed them sometimes,'' he said. ''I feel bad for the little guys.'' But he also admitted: ''I run them out of the train. I don't want them to make no mistakes, if you know what I mean.'' Despite his efforts, they make many little mistakes.

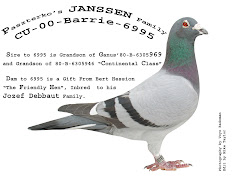

Mr. Rizzo and many of his fellow employees at the terminal have become amateur ornithologists. They said that pigeons -- known vulgarly as air rats, more elegantly as rock doves -- ride trains at several outdoor terminals and stations, like the Stillwell Avenue station in Coney Island.

Francisco Peña, a conductor on the A, said he watched them step off his train and promptly fly back to the Far Rockaway terminal. Perhaps not quite as impressive as the blue homing pigeon reported to have flown 7,200 miles from France back to Vietnam in the 1930's, but still, Mr. Peña said, not bad.

Frank Maynor, a car cleaner, noted how the sparrows and seagulls, also plentiful at the terminal, are never bold enough to venture into the cars. The sparrows can be seen hopping onto the threshold, looking longingly inside. The gulls loiter outside, like thugs, waiting to tear pizza crusts from the bills of unsuspecting pigeons as soon as they carry them out.

''They shove the pigeons around,'' said Mr. Maynor, disapprovingly. ''But they're going to evolve and start going into the trains, too. They're giving up a lot of food to the pigeons.''

On the subject of evolution, Sarah Canty, another cleaner, said she had noticed that the pigeons might be evolving into more alert straphangers. ''When the bell goes off, you watch them,'' she said. ''They know the bell like we do.'' And indeed, when the next bell rang, signaling that a train was about to depart, several pigeons could be seen high-stepping it out of the trains.

But there are those who have either not learned or are yearning to break free from the nest. And at 10:45 yesterday morning, it finally happened: a dark, plump bird with iridescent purple feathers around the neck took a ride. Alone with the bird in the car was Eduard Karlov, a retired procurement officer for the United Nations.

Mr. Karlov, originally from Moscow, glanced over at his fellow passenger and smiled. ''He does not bother me, and, in fact, I find him rather amusing,'' he said, adding, ''I cannot give you any more details with respect to pigeons, however.''

Photos: (William C. Lopez for The New York Times)(pg. A1); With no tokens to its name, a pigeon that got on the A train at the Far Rockaway station in Queens pondered its next move, top. Workers say pigeons often board there and exit one stop later. (Photographs by William C. Lopez for The New York Times)(pg. B3)

Read more ...