By Jackie Kemp

Friday, 4 March 2011

...I marvel at the rapid transformation in the way that news and entertainment are delivered to the public. Yet in their day the telegraph (invented in 1837), the modern typewriter (1867), carbon paper (1872), and the telephone (1872) were just as revolutionary. The arrival of the Linotype machine and the rotary press in the same period coincided with the removal of stamp duty and press censorship.

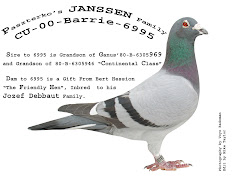

The use of pigeons to carry news also occurred around that time and is part of the folklore of the press. Though I have never seen it they say there is a pigeon loft in the old Herald building in Mitchell Street, which has stood empty since we left it for Albion Street in 1980.

Sometimes, listening to the stories of old-timers, I have found myself feeling a certain scepticism, thinking that perhaps they were apocryphal. Certainly most of the yarns are risible. Yet the use of pigeons for news, documented in various histories of the press, must have seemed during its brief epoch as innovative as fibre-optics in our own time.

It is hard for us to imagine how slowly news arrived until the technological revolution of the nineteenth century. In 1815 the news of Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo took four days to reach London; the news of his death at St Helena six years later was brought by sea and took two months.

Telegraph lines began to spread from the 1840s and, according to a new history of Reuters to be published next week, the use of pigeons sprang up to fill gaps in the chain.

It is often thought that Julius Reuter was the first to employ pigeons in this way but this was not the case. In the field before him were Charles Havas, the founder of the French agency of that name (whose integrity was to be compromised by French Government subsidy), the Rothschilds and other financers. The development of international news services was driven by the need for financial information as well as for political and diplomatic intelligence.

Reuter brought a high degree of organisation to the deployment of pigeons. In 1950 there was a gap of 76 miles between the German telegraph line linking Aachen to Berlin and the French system joining Brussels to Paris.

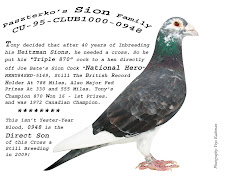

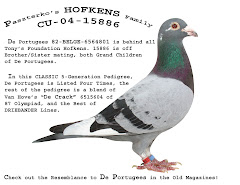

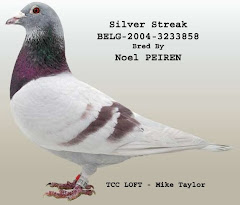

Reuter made an agreement with an Aachen pigeon-fancier who supplied 45 trained birds to maintain a service with Brussels, where they were sent each day by rail to fly back next day.

The first pigeons were released at dawn. To guard against loss or delay, three birds carrying identical messages were sent up each time. A trusted assistant received them in the pigeon loft in Aachen, placing the messages in a sealed box to be sent round to the office where Reuter sat waiting, smoking and reading the papers.

When the box arrived Reuter and his two clerks sprang into action to transcribe the densely hand-written sheets. Runners hurried them to the telegraph office for dispatch to Berlin.

Even in modern times Reuter men occasionally fell back on pigeons in emergencies (for example during the Normandy invasion) but their systematic use by newspapers must have persisted only for some years after 1850.

There was an anecdote on the old Manchester Guardian, where my father worked before the war, about a reporter of the old school who was sent to cover a Gladstone campaign meeting. He went by bike from Manchester to, let us say, Altrincham, and was alarmed to see that a rival had brought pigeons.

Full of despair, he set off back to Manchester as soon as he could, his shorthand notebook in his pocket. As he cycled, the sky darkened and it began to rain. To his immense relief he saw the pigeons of his competitor settle on the dome of the town hall. On that occasion, at least, he was first with the news. No date attaches to this story but it may have been some time before 1867, when Gladstone won a landslide victory and formed his first administration.

Another hoary old anecdote concerns the sports reporter who, towards the end of a local derby in Edinburgh, had written out the scoreline and inserted it under the pigeon's wing. Just before the final whistle, Hearts scored. The reporter (I fear he was biased) raised his arms in exultation, releasing the pigeon prematurely. As it flew off he shouted after it: ''Hearts 2, Hibs 1!''

In those days the pigeon and the telegraph were used to deliver news of national or financial import, of wars and treaties, of markets collapsing or prospering. Nowadays Reuters world-wide system of computer-driven financial information and dealing systems is of first importance, a vehicle for the currency flows which so inconvenience national governments from time to time. In the sixties the volume of foreign exchange transactions was about $3 trillion a year. By 1987 it had reached $87 trillion, a staggering rate of growth.

Much of the new information technology delivers entertainment or trivia across frontiers, reinforcing American domination of popular culture. But even in the old days the cabled message could be vacuous, as we are reminded by the couplet on the illness of the Prince of Wales by Alfred Austin, whose appointment as poet laureate in 1896 aroused widespread derision:

Across the wires the electric

message came:

He is no better, he is much

the same.

Then, as now, the means to communicate provided no guarantee that there was anything to say.

Read more ...