Naturenews

Janelle Weaver

Published online 7 April 2010

During flight, pigeons in a flock follow the leader.

Birds of a feather follow the leader

.A. Gehrig/ iStockphoto

Pigeons wearing miniature backpacks containing tracking devices have revealed that the birds rapidly shift direction during flight in response to cues from the leading members of their group.

"It is the first study demonstrating hierarchical decision-making in a group of free-flying birds," says Tamás Vicsek, a biophysicist at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest who led the study, which is published today in Nature.

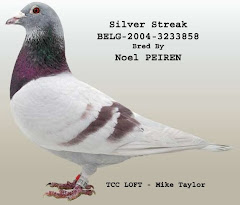

The discovery became possible only recently with the introduction of Global Positioning System (GPS) devices that can collect data at a high rate: five times per second. Vicsek's team strapped lightweight GPS devices to individual pigeons and tracked flocks of up to 10 birds during free flights lasting around 12 minutes and 15-kilometre homing flights. In total, the GPS logged 32 hours of data and captured 15 group flights. The researchers couldn't pinpoint individuals' exact positions within a flock, but were able to accurately compare birds' directions of motion.

Within flocks, the authors looked first at the behaviour of pairs of birds. For each possible pairing, the team identified a leader — the bird that changed direction first — and a follower, which copied the leader's motion. Followers reacted very quickly, within a fraction of a second.

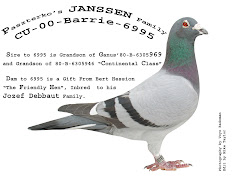

Pigeons carrying miniature GPS devices have helped to clarify the complexities of hierarchy in homing animals.

Z. Ákos

Next, the scientists constructed a network of relationships among birds in the group during each flight. They uncovered a robust pecking order: birds higher up the ranks had more influence over the group's movements, and each individual's level of influence was consistent across specific free and homing flights.

However, this influence was not always consistent between flights, with some rearrangement occurring among birds at the head of the flock. Vicsek speculates that this may have occurred because an original leader had tired. Co-author Dora Biro, an animal behaviour expert at the University of Oxford, UK, says, "This kind of group decision-making is more complicated than previous models suggested."

Follow the leader

Although pigeons have an almost 340º field of view, the researchers found that the birds at the front of a flock tended to make the navigational decisions. Moreover, birds responded more readily to a leader's movements if the leader was on their left side. These findings concur with previous work that indicated that social cues entering a bird's left eye receive preferential processing in the brain.

"No other study has contributed more to our understanding of collective decision-making in actively homing animals, not by a long shot," says Todd Dennis, an expert in pigeon navigation at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. He likens the birds' group behaviour to that of a cabaret dance troupe, in which less-experienced dancers towards the rear correct themselves by watching experts at the front. "The study provides a very important model for how collective behaviour and leadership can be assessed in a range of animal groups," he says.

The authors say that a hierarchical arrangement may foster more flexible and efficient decision-making compared with that of singly led or egalitarian groups. In future studies, the scientists plan to investigate whether leaders are better navigators, and whether hierarchies persist in larger groups and in other types of social animal. "If it's true that there's an evolutionary advantage to making decisions in this way, then there's absolutely a reason to assume that it could have evolved in other species too," Biro says.

Read more ...