Sunday, May 22, 2011

By Susan Banks, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

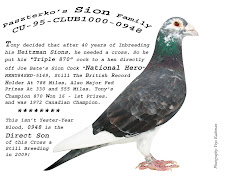

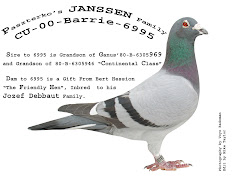

An Elston Trenton racing pigeon at Ron Goebel's loft.

What do the Queen of England and Mike Tyson have in common?

Pigeons.

The queen keeps a loft at Sandringham Castle and Mr. Tyson keeps his birds in New York and Las Vegas. Mr. Tyson recently starred in the Animal Planet series "Taking on Tyson," which followed his attempt to cobble together a winning racing pigeon loft in one season.

No one knows if the former boxer can find the redemption he seeks through birds, but locally the show has been embraced by pigeon fanciers who say it has brought positive attention to their hobby, in spite of Mr. Tyson's unsavory reputation. The irony here is the birds are probably as demonized as Mr. Tyson is, often called "flying rats.

Finding pigeon enthusiasts in Pittsburgh isn't hard after you locate Foy's Pet Supplies. In 2000, Jerry Gagne (pronounced "GONE-yay") became the third owner of Foy's, which has been catering to pigeon fanciers since 1887. The business is in a small storefront and warehouse in Beaver Falls, from which Mr. Gagne sends mail-ordered supplies, including fully built coops, all over the country. He also sells birds -- pigeons can be sent next-day air via the U.S. Mail.

While Mr. Gagne once raced pigeons, the business now keeps him and his family pretty busy and out of the racing game. Yet he is the common denominator when it comes to pigeons in Pittsburgh. If you race or show them, you will at some point wind up talking to Mr. Gagne, who is a wealth of information on pigeon care and knows most local pigeon fanciers.

Mr. Gagne says show pigeon fanciers probably outnumber racers in the area. These birds are exhibited in events much like AKC dog shows, where the conformation of the bird is judged. Because these pigeons, with a few exceptions, are not flown and therefore don't have to be trained and conditioned, it is much easier and cheaper to get started with show birds.

Pittsburgh racers

Racing pigeons have a much longer history in Pittsburgh, and not just as the closest relatives of the unwelcome pests that roost Downtown. By the 1870s, racing clubs had been formed on the East Coast and were most certainly in the Pittsburgh area, coming west with immigrants arriving to work in the steel mills. It is unlikely that they brought pigeons with them, but once they settled, they began importing birds from Germany, Holland, France and Belgium, places that even today are hotbeds of pigeon racing. It was once the national sport of Belgium.

In the 1930s, a local "flyer" from the small river town of Glenfield by the name of Harry Elston began making pigeon history. His strain of a breed called a Trenton were regularly winning races, some from distances of 1,000 miles and more. Some of the records his birds broke have never been bested. By 1936, Pittsburgh had the largest number of flyers in the American Racing Union and bragging rights from winning many prestigious races.

By some estimates, there were 600 racing lofts in the area in the '70s, and it was not uncommon for Pittsburgh to send 10,000 pigeons to an event.

These days, flyers, as they refer to themselves, are still found locally, just not in the number they once were. Those who remain are just as serious about the pursuit as their forefathers.

Family of flyers

Bob Kelvington, Nathan Lex, and Karl Lex

Karl Lex and his son Nathan can't remember a time when pigeons weren't in their family. Third- and fourth-generation flyers, respectively, they may have been genetically disposed toward the birds.

"That's all I remember from day one. ... I always raced with my dad," says Mr. Lex, who is now 58.

His late father had a loft on Spring Garden Avenue in the North Side, and Mr. Lex had a loft on Mount Troy Road in Ross.

In the late '50s and early '60s, the closest pigeon club to the Lex family's was on Troy Hill in the North Side. There was another in Lawrenceville, but the Lex family flew from a club on Spring Hill: the City View Keystone Club.

"We had maybe 40 or 50 members," says Mr. Lex. "We would ship 1,000 birds [to a race] on a weekend, and there were other clubs."

Mr. Lex now flies with his 28-year-old son, Nathan, and partner Bob Kelvington. Nathan Lex took to the birds immediately.

"Ever since he could walk, he'd be in the [lofts]. You couldn't get him to come out of there," says his father.

Nate is now the youngest member of the Tarentum Club. His brother and sisters have no interest in the sport, which sadly is becoming the norm.

The three men compete during the spring/summer racing season out of the Tarentum Homing Club, which has about 20 members. They fly against about 35 to 40 lofts from the region, which also encompasses parts of eastern Ohio. The Lex loft is now at Mr. Kelvington's home in North Sewickley, Beaver County. They currently have about 200 racing homers.

Keeping a loft of competitive racing pigeons entails work and dedication. The animals need to be kept clean, healthy, trained and conditioned. Races begin around the last week of April and are held weekly throughout the summer.

"They are left out every day," says Karl Lex. "They are navigating, learning how to hit the coop. They are also developing and building muscle."

Serious training begins at about 4 months. When road training starts in the spring, the birds are driven away from the loft in incremental distances, released and allowed to make their way back.

Races are grouped into old bird -- any bird more than 1 year old -- and young bird. Old bird races began in April and young bird races start in late August. Distances are increased each week, up to about 550 miles -- the distance a pigeon can fly in a day. Pigeons are usually raced competitively until they are 5 or 6 years old, but can live to be 15 or more in captivity.

While the Lexes and Mr. Kelvington sell a few birds yearly, they are quick to say that they do not view their pigeons as a money-making enterprise. Instead, they take pride in the multi-generationality of the pursuit and the satisfaction they get from breeding winning birds.

So important are the birds to them that when Mr. Lex's father passed away, feathers from a few of his favorites were placed in the casket with him.

Pedigreed pigeons

Ron Goebel, 75, of Cranberry has spent a large part of his life in the company of pigeons, beginning when he was growing up in Troy Hill. While nobody in his family kept birds, many neighbors did, and Mr. Goebel did what many kids of that era did: He hung around the coops.

His first bird, given to him by a neighbor, was lodged in the case of an old radio. Even though he didn't win a race until 11 years later, he stayed with it.

Mr. Goebel coveted Elston Trentons, bred by Harry Elston of Glenfield, and Glassbrenners, a strain developed by the four Glassbrenner brothers of the North Side. Mr. Elston's pigeons won so many races in the '30s that finally many of the local clubs would not allow him to fly with them.

"They like you until you win too much," Mr. Goebel says with a smile.

He was never able to purchase birds from Mr. Elston, who died in 1960, but he did track down birds with lineage from his loft. He located and bought some Elston Trentons from a flyer in Clinton, Ark., in 1989. In 1992, he located another flyer living in Fond Du Lac, Mich., who had some birds, and finally, obtained some from a friend in Hopewell.

"I have Elstons from three different sources, and this is a good thing as it gives some diversity in the gene pool," he says.

Older birds are purchased for breeding purposes only. They are not raced because they will return to their "home" loft -- the place they were trained from.

As for the Glassbrenners, his uncle gave him six birds for his birthday in 1953. In 1980, Frank Domke, now 94 and living in Naples, Fla., gave him some that he didn't take with him on his move south. He got another 20 birds from him in 1989, and in 2004 Mr. Domke gave him a few more birds while he was visiting him in Florida. Mr. Domke just recently gave up the hobby.

Though Mr. Goebel has not raced his birds since 2000, he keeps both types in his Glen Eden loft, where he fusses over them daily. Like any type of animal breeding, pedigrees are important, and he is a stickler for keeping the lineage of his birds written down.

His home is a treasure trove of pigeon lore. He's kept pigeon periodicals from the '20s, including daily newspapers, which at one time published racing results. He has several antique timers, which used actual watches to time the birds. Modern timers employ chips embedded in the bands fastened to a bird's leg. The timer registers when the bird "gates" through the loft door. These mechanisms can cost $1,000 or more.

In the 1920s, people would take the birds to the train stations and send them out on the rails for training. By the '50s, there were so many people racing birds that you could take them to a central location and for a small fee, perhaps 10 cents a bird, trucks would take them out to appointed distances and release them.

Now, says Mr. Goebel, pigeon owners must transport their own pigeons. Daily road trips are necessary during training, making rising gasoline costs just another impediment to getting started in the pursuit.

Zoning ordinances are also an issue. Where lofts once peppered the hills and valleys of the region, they are now prohibited in many areas. Mr. Goebel doubts that pigeon racing will ever achieve its former popularity.

His own goal is simple: "I am determined to keep the legacy of the Glassbrenner brothers and Harry Elston going to the next generation."

His own will is clear: His beloved pigeons will be left to his grandson.

Queen of the coop

For some reason, pigeons and women don't often mix. While both male and female pigeons are raced, women are not usually involved.

But there is always an exception: Patty Polka, 48, of Leechburg is giving racing a try for the first time this year. She hopes to have birds ready to enter in the young bird races that run from August to October.

Her father, Ted Polka of North Huntingdon, raced pigeons from the time he was 5 or 6 until the care of the birds got to be too much for him, which is often the case for many flyers. Ms. Polka had helped her father with the birds, as did her sisters. She is the only one who races.

"At first I wasn't sure," she says. "The more I worked with the birds -- you get sucked right in. They are beautiful creatures and intelligent."

She lives in a rural area, so having a coop wasn't a problem, but she also cleared it with her neighbors. She currently has seven show pigeons (Birmingham Rollers) and some homers. She has also accumulated some breeders, saying the hobby is more addictive than you might think.

"Everybody is telling me I need a minimum of 20 (to race), but I'm only going to start out with 14 because I don't have a clue what I'm doing," she says.

She joined the Tarentum Club and its members have been helpful, she says. She thinks more women are involved in pigeon racing than you might think.

"I can probably guess that a lot of guys in the club get their wives to do a lot of the work," she says, laughing.

Read more ...