VPR News

Vermont Public Radio

Steve Zind - Williston, VT

Thursday, 09/13/07 5:33pm

(Host) Today take a glimpse at a disappearing pastime: the sport of pigeon racing.

"What's with the birds?"Well they're messenger pigeons. I'm going to release them and whichever get home first I'll enter in the county fair." "Pigeons, huh?"

(Host) That's a clip from Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Even in the 1930s, Jimmy Stewart's trained pigeons didn't make much of an impression on the city folk. But all these decades later, pigeon racing is still alive and well.

On weekends, a group of Vermont enthusiasts pack up their birds and ship them off to distant locations in hopes they'll return home safely and swiftly.

As VPR's Steve Zind tells us, there's more to the sport than meets the eye.

(Zind) Tell Dick Zutell that his racing pigeons resemble the ones that you see begging for handouts in the park, and he'll give you a tolerant look.

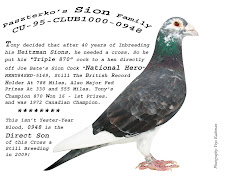

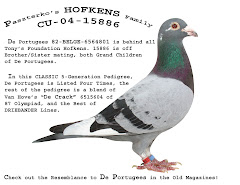

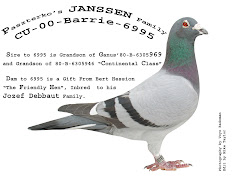

(Zutell) "They look like the park pigeons, but they're not. We could tell you the pedigree and the lineage behind every pigeon, I mean back 50, 60, 100 years."

(Zind) Zutell and a few other racing pigeon enthusiasts have gathered in Williston with their birds in cages. They're being be loaded into a trailer and shipped to New Jersey, where they'll be released to race back to their owners in Vermont.

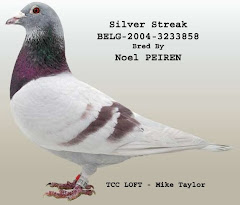

These young pigeons were born in the spring - breeding them from proven racers is part of the art of the sport. All summer they've been pampered and prodded to fly fast.

Their race from New Jersey is the culmination of a summer of training that involves taking them out daily; first just a few miles from home and then further, to teach them to fly back to the roost. When they return, they're fed and coddled to reinforce the idea that coming home quickly is good, and chillin' with those pigeon n'er do wells in the park is not good.

(Zutell) "If they're going to sit down there and talk to their neighbors, no. We want them to race home."

(Zind) In the parlance of Zutell and his fellow pigeon racers, it's not just the birds who do the flying.

(Zutell) "I started flying in ‘47. I was 13 then. I belonged in a club in New Jersey. There was just a lot of flyers back then, there's not now. It's a dying sport and it's a shame."

(Zind) Zutell says there are just a handful of pigeon racers left in Vermont. Like him, many belong to the Champlain Valley Racing Pigeon Club. The sport probably reached its modern day peak in this country in the 1950s. The birds were used to carry messages during the Second World War and returning soldiers brought home an interest in racing them.

Peter Sapienza is a rare newcomer to the sport. Sapienza says he was attracted by the bond that develops between bird and flyer.

(Sapienza) "It's just a really full relationship with the birds who are coming back to be with you and to be in the loft. One of the things you need to work on is motivation."

(Zind) Motivation. That's where knowing a bit of bird psychology comes in. Pigeon racers fly both the male cocks and the female hens. In the hen, the maternal instinct is strong. Her desire to take care of her eggs makes Dr. Seuss's egg-hatching elephant Horton look like a slacker. To get a hen to fly home as fast as possible, interrupt her egg sitting duties and then send her off to race home.

Sapienza says flyers even try fooling the hen into thinking her egg is about to hatch.

(Sapienza) "People have been known to take little plastic eggs and put a fly in it and put it in the nest under the hen so that it rattles a little bit and will motivate her to come home."

(Zind) It takes about 7 hours for a good racing pigeon to fly the 250 or so miles from New Jersey to Vermont. For the victor, there's no prize money or trophy - just the satisfaction of having raised a winning pigeon, and the enjoyment of the sport

(Sapienza) "What we're out for is because we love the birds."

(Zind) For VPR, I'm Steve Zind.