By Paul Terefenko

Now Toronto

Pigeons are the victims of bad PR by pest control companies cranking out propaganda

You probably didn’t see many pigeons this week as wintry blasts sent a blanket of snow over city streets, but the tenacious feathered omnivores remain here, huddled furtively under rooftops.

Not that their presence gladdens absolutely everyone.

The reality is, there’s a megabucks industry in Toronto with unrestrained rights to poison the creatures and the ecosystem – and nature lovers can’t figure out why no one’s squawking.

It doesn’t help that pigeons, sometimes called rock doves, just can’t get good PR. There’s even a name for the disgust they engender: “peristerophobia,” or fear of pigeons. Certainly, it’s hard to earn a noble perch when munching on our discarded pizza crusts and half-eaten doughnuts. But to be fair, they only have 37 taste buds – with our 10,000 we should really know better. And they’re keeping our rotting trash off the sidewalk.

Finding folks who want to get rid of them is eerily easy. At the mild end of the anti-pest continuum is Christian Szabo, owner of Pigeon Busters. He tells me he has products that protect window sills, ledges, store signs – non-lethal electrified or spiked strips aimed at deterrence. “An electrical track shocks them and teaches them to stay away,” he says.

It gets much worse, though. If you’ve see a bird flipping out on a Toronto sidewalk, the culprit could be a poison like Avitrol. This odourless chem, mixed with corn, is banned in most of Europe but still legal here.

Not that exterminators aren’t sensitive about laying poisons about. Julian Compton, service manager at huge multinational Rentokil, says his company generally tries to steer clear of chemicals because birds are “prettier than rats and mice, so in the public eye you have to be a damn sight more careful.”

That said, there are occasions when the company still uses Avitrol, even though Compton has some doubts about its effectiveness. What it does, he says, is induce fear in other birds when some of them start convulsing. What he doesn’t mention is the fear it should induce in all vertebrates. It can mess with our nervous systems, too.

Another chemical used in the war on pigeons is Ornitrol, which suffocates developing bird embryos, though it’s also only partly effective.

So who’s monitoring these nasties? Toronto public health spokesperson Susan Sperling says it’s not her department and refers me to higher powers.

At the Ministry of the Environment, spokesperson John Steele tells me only licensed exterminators are permitted to use Avitrol. Label directions, in accordance with Health Canada’s pest management regulations, he says, indicate proper use so non-target birds, pets and children don’t come in contact with the poison.

Ultimately, those concerned with easy pigeon control will reach for their guns, says Compton. “There are laws against the use of guns in Toronto,” he says, but there are air rifles that are legal for use on private property.

“If you shoot a handful of birds, you get rid of the problem in a short time. It’s basically the most efficient way,” he adds. He’s not talking deterrence here – he means efficiently dead.

“It’s really a licence to print money,” says Merchant. While killing part of a pigeon population gives the impression that their numbers are reduced, he says in reality it increases the culled population by 15 to 30 per cent.

“If contractors kill, for instance, 50 per cent of a flock, they go into breeding overdrive,” he explains. Other flocks also see bird movement to the newly available food sources, and breeding increases in those vacated flocks as well.

Exterminators know this, Merchant says, and capitalize on it. “Companies are killing birds for their clients on the understanding that the problem will be resolved, when in reality their practices are simply further entrenching the problem. They provide themselves with a job for life.”

It makes sense. We haven’t seen a marked decrease in pigeons, and contractors I talked to said the situation is stable. Not one of them could give me any numbers on population decline.

And this creates another circular problem – there’s always an abundance of pigeons, and most people are only moved to defend rare birds. Liz White of Animal Alliance explains the dilemma: “If there are too few of a species, we love them. If there are too many, we try to get rid of them.”

But, she says, “we have produced, as a society, a carrying capacity that pigeons can survive in.”

So what exactly is the downside of sharing the city with pigeons who use our buildings as if they were mountain ledges. Well, their acid guano does accelerate the erosion of building materials, while interfering with the aesthetics of our edifices.

But Merchant has spent 35 years fighting to clear the air on the most potent charge against them: that their poop can make people sick. Mere pest industry hype, he says.

“There is a far greater likelihood of someone catching a disease from eating factory-farmed chicken,” he says.

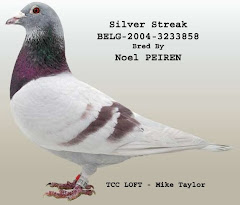

He goes on to enumerate the ways people have traditionally relied on pigeons: for food, for communication (Reuters used them for news, the Rothschild family for financial communication) and to save lives in wars.

“As soon as we don’t need them any more, because technology takes over, we wipe them out. If anybody’s to blame for pigeons overpopulations,” says Merchant, “it’s people who feed them and the pest control industry.”

Read more ...